Two rivermen “tending out” (keeping the logs flowing) at a bad place on the South Valley Branch of the Swift Diamond Stream in Maine. c. 1939.

Pike, Robert E. Tall Trees, Tough Men W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1967.

| Featured

Re-using any thing – the back side of scrap paper, buying a vintage shirt, installing deconstructed cabinetry – can seem an environmental no-brainer. And just the same, why cut down a good tree when there’s ready-made lumber from a felled building down the street?

The benefits seem even clearer with other raw materials. Scrap iron, for instance, requires just a third of the energy to recycle as virgin ore fed into a blast furnace to make new steel. The energy factors look flipped on the farm as well, where energy used to make food is all but a small percentage of overall fuel needs.

Scrap lumber and new logs are run through similar sawmill process’, even if the scale of operation is different. And demolition and forest logging look comparable on an energy count. And trees, of course are renewable. So new and used lumber on look to part ways from a carbon standpoint when the truck leaves the sawmill – aside, of course from the issue of having felled a new tree and sent an old one to the landfill.

Are sustainably harvested logs better or worse for the environment than salvaged lumber trucked or shipped from a far off region? A carbon footprint analysis should yield some rough idea, but no matter the relative measure, they both seem preferable than the wood coming out of the big box stores. Home Depot, Lowe’s, Ikea and Walmart all acknowledge that they are not yet able to track the wood sourced from over 80% of their Far East suppliers; an astonishing volume considering how much illegal timber is known to be flowing across the Russian border and out of Indonesia.

But reclaimed wood products, often priced 50% higher (at least) than new lumber, force many to justify that value on more than environmental grounds. Fortunately, reclaimed woods go well beyond the carbon footprint factors, being crafted by nature like the finest hand made shoes. The material maintains it’s value over time, trading on a mix of real world and esoteric qualities that combine quality, design (richer grain figure, color, character marks, etc) sustainability and the allure of history, into materials we can feel good about.

| Featured

The Locavore’s Dilemma: In Praise of the 10,000 Mile Diet, by Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu attempts to debunk the most heartfelt beliefs of the local food movement. The counter arguing tone gets a kick-start in the introduction by an actual Missouri industrial farmer, and then goes on to take academic pot shots at the far left and agri-intellectuals, which, depending on the case, or relative position on the political/philosophical spectrum, are alternatively benign, counter-productive or outright dangerous.

The Locavore’s Dilemma: In Praise of the 10,000 Mile Diet, by Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu attempts to debunk the most heartfelt beliefs of the local food movement. The counter arguing tone gets a kick-start in the introduction by an actual Missouri industrial farmer, and then goes on to take academic pot shots at the far left and agri-intellectuals, which, depending on the case, or relative position on the political/philosophical spectrum, are alternatively benign, counter-productive or outright dangerous.

They target foodies and urbanites that get a fix from the agrarian charms and tastes of farmer’s markets, heirloom varieties and organic produce; and the far left, often the low hanging fruit in assuming self-righteous anarchist opposition to industrial farming and globalization (a different kind of critique than the antics of Portlandia); and in the process, dismissing or underestimating the real virtues and intangibles that may amount to simply a more elevated form of eating – no small part of society – in the future. Or that local food production may still be at the beginning of a long trajectory. By contrast, Desrochers and Shimizu celebrate free markets and the global food chain – an evolving system that has nearly abolished hunger, improved food safety ten-fold, and delivered a bewildering variety of meat and produce to the local supermarket. But the argument seems out of balance, nearly as hard line as those being targeted (even if they’re just trying to make a point – or worse, goaded by the publisher to pick a fight) – that the potential for the best of both worlds seems lost.

Which side of the argument, or in what degree, local v. global develops is hard to know. The reviews are divisive. A lumber company blog isn’t the place for an analysis of the food safety, economics and environmental issues swirling within the complex world of local food. Maybe just how the analysis translates to “local lumber”.

| Featured

| Featured

| Featured

With the relatively recent establishment of the U.S. Green Building Council and the LEED standard, it can seem far reaching to consider sustainable architectural practices in the early 19th c. The architect at the center of that prospect, Ithiel Town, would found the country’s first architectural firm, Town and Davis on Wall St. in 1828. A Pioneer in American Revivalist architecture, taking on a commissions in the neo-Greek, Egyptian, Gothic, Tuscan and other styles, the architectural historian Talbot Hamlin would go so far as to call Town “One of the most important personalities on the American scene in the second quarter of the 19th century.”

There’s evidence to suggest that Town had a growing awareness of environmental issues, and that strategies in his architectural practice represented a conscious response. It is impossible to measure Town against modern green building, or to expect that environmental damage such as acid rain, global warming, VOC contamination, etc. – could have been foreseen at that time. But the rate of deforestation and early effects of the Industrial Revolution were beginning to raise alarms related to the environment. Research is currently underway to uncover what remains of Town’s environmental record. Sustainable architects today may yet have something to learn, or at least feel confirmed, from America’s earliest professional architects.

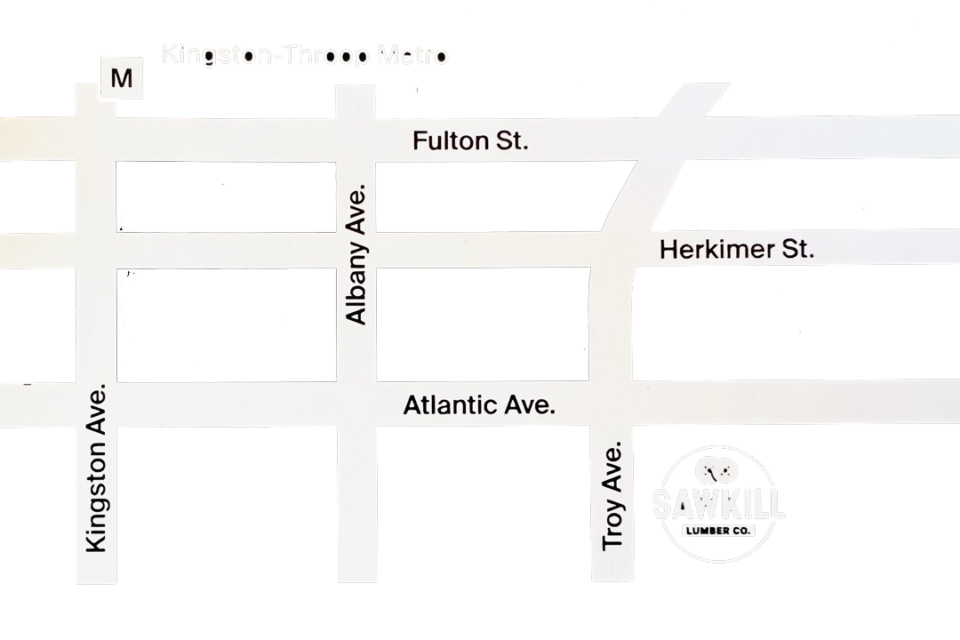

Our location at 71 Troy Avenue in Brooklyn includes a showroom, and a 3600 sf warehouse and wood shop. We are currently open for meetings by appointment. The space features a broad selection of over 40 antique, vintage and rare reclaimed woods.

(917) 862 7910

info@sawkill.nyc

Mon.-Fri. 9:00 – 5:30 pm

Sat. 10-4pm

1 Troy Ave.

Brooklyn, NY 11213

Please call in advance for appointment!

Getting There:

Train: A, C to Utica Ave. train stop. (approx. 8 min walk)

Car: Atlantic Ave. to Troy Ave. (1.5 mi. from Barclay Center)