Uncategorized

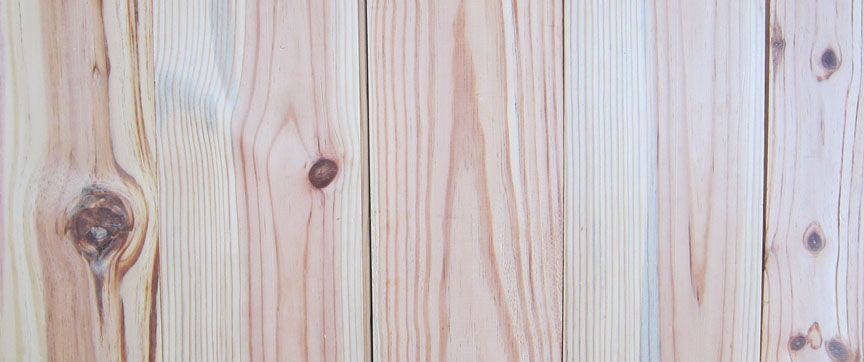

Mid-Century Reclaimed Pine

Sizes: 1/2-4/4″ x 3″ x 8″ widths x 3-14′ legnths

Applications: Paneling, flooring, furniture.

Defining Characteristics: Mix of darker heart wood and lighter tone sap wood, flat and vertical grain, broad growth rings, above average knots, infrequent nail holes.

Second growth lumber, harvested after the old forests had been logged, and often gets passed over by connoisseurs as the cheap wine of the reclaimed wood world, appreciation siding the dense clear grained and darker hued woods. But second growth, primarily found in conifers like Southern Pine and Douglas Fir, has gained a fan base in recent years, making it deserving of a second look.

Quality– Second growth trees didn’t need to compete for light and nutrients like the high density zones of an old growth forest, leaving it with a lighter broader and softer grain, but on one level, the different is purely aesthetic and subjective, like the preference for broad or fine strokes in a painters style. The broader look may fit a different design vision, bring out a stain or pick up dents and dings in a desirable pattern. And it doesn’t loose ground on a wider and longer plank look that is a staple of reclaimed. Price wise, it’s alway at least 25% lower.

History – Second growth woods rose after the old growth had been felled, around the turn of the century. The trees rose in sparser forests in just a fraction of the time – about forty years or more. Their lumber went into mid-century construction, carrying the provenance of that era. It may not evoke the same mystique as late 19th century woods, but it can have it’s own allure, like the modernist charms of things vintage.

Sustainability – Pound for pound, second growth lumber is still wood, still reclaimed. It’s environmental value in being salvaged is no different than other grades and species. Possibly greener, if you consider that they’re more vulnerable to conventional disposal. The architects and designers that work with lemons and regularly make lemonade have produced some striking work with reclaimed second growth, saving clients some money, and perhaps a few additional trees.

Naily Heart Pine

Sizes: 1/2″-4/4 thickness x 3-9″ widths x 3-16′ lengths

Applications:Paneling, flooring and furniture.

Defining Characteristics: Deep amber color from saturated oils, tight heartwood figure, occasional nail holes, sound tight knots.

After old wood is re-surfaced, the clearest sign that it’s reclaimed are the nail holes, framed with a dark ring that looks like a permanent black eye. The distinctive mark results from the century long decomposition of old iron (before harder steels were achieved around 1890) which bleeds into the surrounding wood fibers. The reproduction world hasn’t bothered trying to make faux iron-stained nail holes.

Nail removal takes time and labor. All salvaged lumber passes through the metal detector; it searches for broken off nails buried under the surface, and sets off a beep, familiar to both Homeland Security personnel and scrap wood de-nailers, when it picks up a piece of ferrous. A range of hand tools are then set into motion: cat paws, chisels, hammers, vice grips and an ingenious old devise called the “Crescent Nail Puller”. Seconds, sometimes minutes later, just a tiny specimen of metal is pulled out. But that’s all it takes to force a blade change.

The dark nail hole is a portal to the woods past. A 19th c. manufacturer (possibly from Birmingham or Sheffield, England) cut a tapered square “Class B” nail from a sheet of iron and forged on it a tiny head, shipped it off to a New-York hardware dealer (early at Pearl and Platt Street), where it was sold at auction to building suppliers in other areas of the city (and developing continent). At some point, a builder banged the nail through a floor board and into a freshly sawn joist below. A hundred and twenty years later, it will see the light of a 21st century city. Nail holes carry their own mystique, the smallest residual connection with the industrial revolution.

A board with a heavy nail pattern is sawn off the face of upright columns that were post-it boards for the 19th c. factory, or from joist edges where flooring was nailed to the sub-structure. A tight rich grain can also characterizes naily boards, since it represents the outer rings of a tree, which grew no thicker than a pine needle in burgeoning old forests.

Skip Planed Heart Pine

Sizes: 3/4 – 3″ thickness x 3-12″ widths x 3-18 lengths

Applications: flooring, paneling, cabinetry, furniture.

Defining Characteristics: Deep brown and amber hues, Rustic old growth surface, saw marks and light surface checking.

Naily Spruce Sheathing Board

This wood supposedly came from a mid-nineteenth century church. Most of the

church was constructed of white pine with a very small amount of white oak

and this spruce sheathing. As with most churches I’ve seen in the past,

there was clearly a sincere effort to construct the structure with the best

available materials and the finest craftsmanship. Although this spruce was

not especially prized then, its heavy thickness and tongue and groove

milling make it atypical for sheathing from this era.

Application: this wood is very dark and very naily, making it ideal for the

right paneling or flooring application if some denting can be tolerated.

Dimensions: thick 4/4 can be used as is or resawn into a very thin paneling.

Most is 7-9″ wide. Random length to 16′.

Defining characteristic: very dark and extremely naily make it very

primitive looking.

Sunken Pine

Sizes: primarily 4/4 with some 5/4, 6/4 and 8/4. Primarily 4-11″ wide and

8-12′ long.

Applications: ideal for flooring, paneling, furniture as well as all other interior

applications.

Grade: character or clear grade, sound tight knot. No nail holes, very limited

checking.

Defining characteristic: unusual coloration from being under water so long

Milling and texture options: planed surface Grain density: about average for

heart pine, not loose but not especially tight either.

During the heyday of the industrial revolution most of the 100 million acres

of the original long leaf southern yellow pine forest was cut down. The

logs were often transported to local mills via river. Along the way, as

many as ten percent of them sank. These sinkers were usually dense young

trees. Young trees have a higher percentage of live sap wood and therefore

a higher percentage of water, making them heavier and more susceptible to

sinking. Many of these logs were axe cut and some had a chevron cut into

them to pull the turpentine out while they were still standing. The logs

this wood came from were pulled from Cape Fear in South Carolina.

Unlike heart pine from industrial timbers, sunken heart pine has been

absorbing the minerals of the river bottom for over a hundred years. Black,

green, brown and grey tones wash into the previously vibrant red and gold of

virgin heart pine to create a muted, dark tone; while the characteristic

grain of heart pine remains as bold as ever.