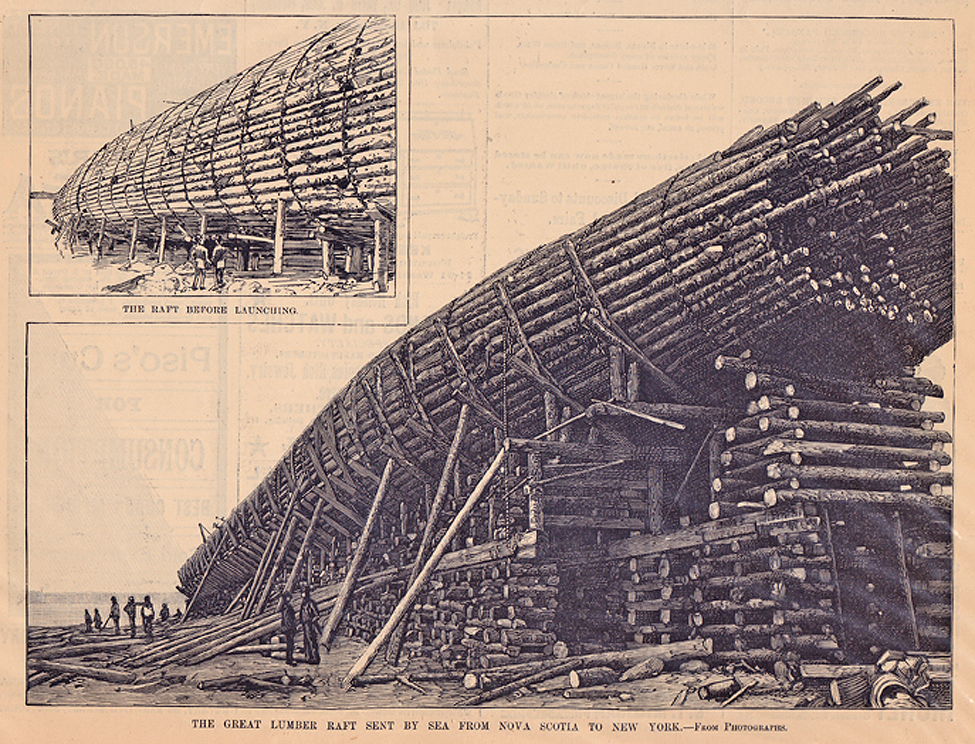

Nineteenth century warehouses, mills and factories can almost appear over-built, utilizing massive dimensional timbers as upright columns and cross beams between rows of smaller joists, designed to handle bulk goods and heavy machinery. As in residential, White Pine was the early standard for commercial buildings in the Northeast – though builders took a decisive turn towards Longleaf Pine by the late 1800’s, as the the towering Southern evergreen yielded large and straight dimensional lumber, while being rich with resin, a natural repellant of rot, and more importantly fire.

The vast reserves of Southern Pine were as eagerly harvested during the industrial revolution as the iron ore deposits of Pennsylvania. You can see this transition to Longleaf Pine built into the geography of Manhattan, where White Pine may be found in the older parts of the island (especially in the South Street Seaport area), with Longleaf Pine the standard of cast iron buildings in todays Tribeca and Soho, when steam power made it possible to navigate the strong currents on the West Side.

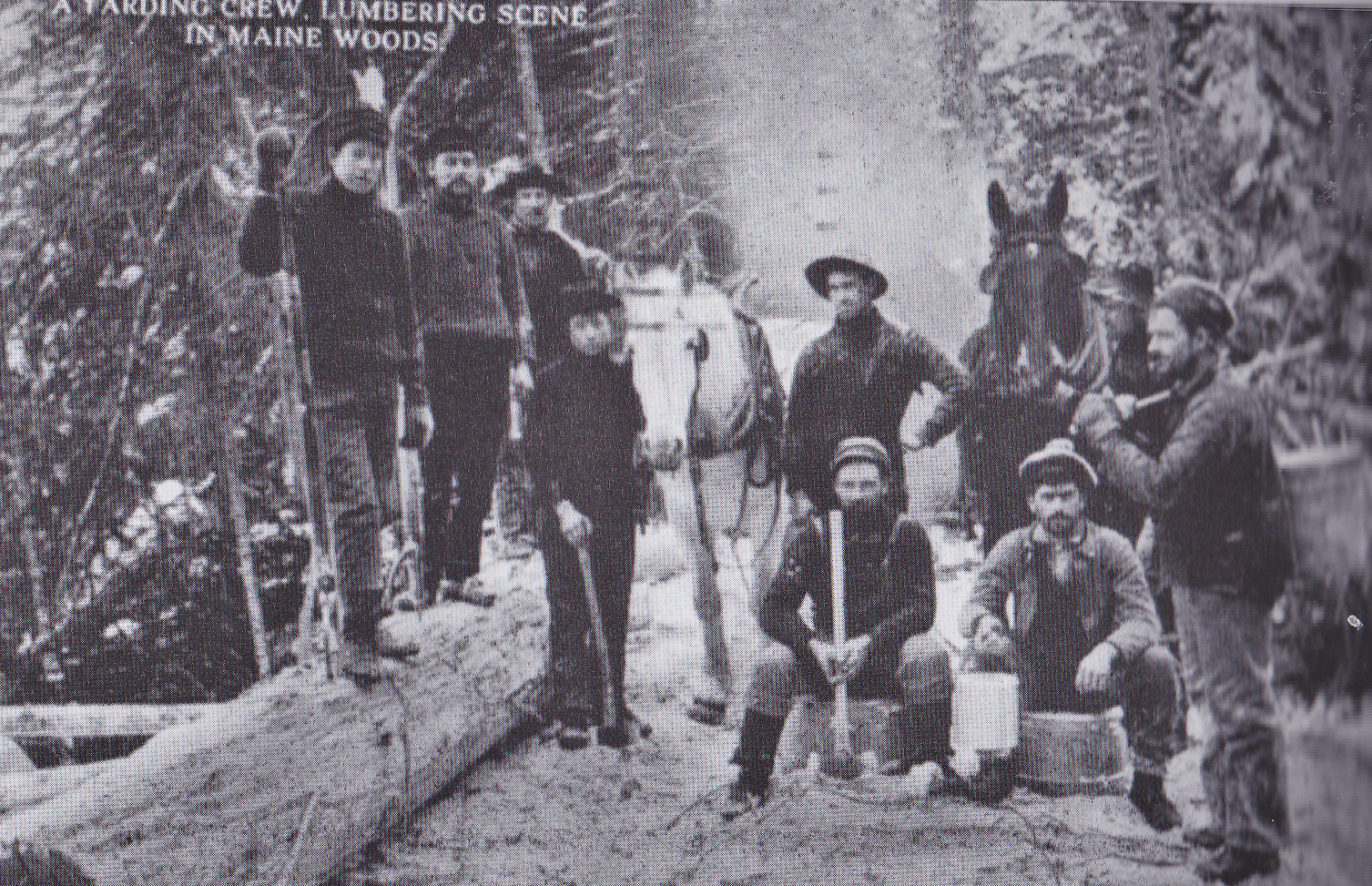

Industrializing areas all along the Northeast appeared to follow a similar pattern; making Southern Pine (largely financed and operated by northern timber companies), the signature wood of the industrial revolution. Generally the heavy framework is layered with a thick Pine decking of 2-3” and topped with hard maple, both of which are commonly salvaged today.

Other woods turn up, though in different regions or eras. For instance, a range of other Southern and Western Pine species, related but not as hard as Longleaf. Loblolly, Shortleaf and Red Pine can be found in the mid-Atlantic and other areas. And by the beginning of the 20th c., the roads opening to the massive Doug Fir forest of the Northwest.

Wood Species: Longleaf Pine, Shortleaf Pine, Eastern White Pine, Douglas Fir.

Sizes: 3-16” thickness’ x 10-16” widths x 15-30’ lengths

Defining Characteristics: Huge dimensional sizes: Rough sawn or circular sawn surfaces, Dense old growth figure.