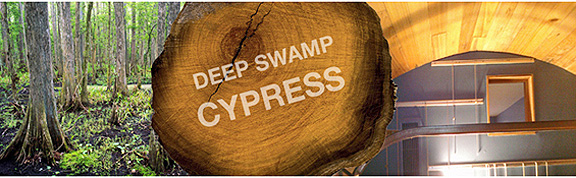

Storied Boards NYC documents the history of lumber that is salvaged from dismantled structures in the New York City area. The research follows the journey of a log, from it’s evolution as a tree species to a building and design project in the 21st century. The scope of the research involves the natural history and anatomy of the original trees, early American logging and lumber industry, construction techniques, the individual buildings and structures where woods are reclaimed and related areas. Tracking re-uses of the lumber to new building and design projects maintains a living history of the this rich and authentic form of material culture. Research for each of the structures is a work in progress conducted by the research team.

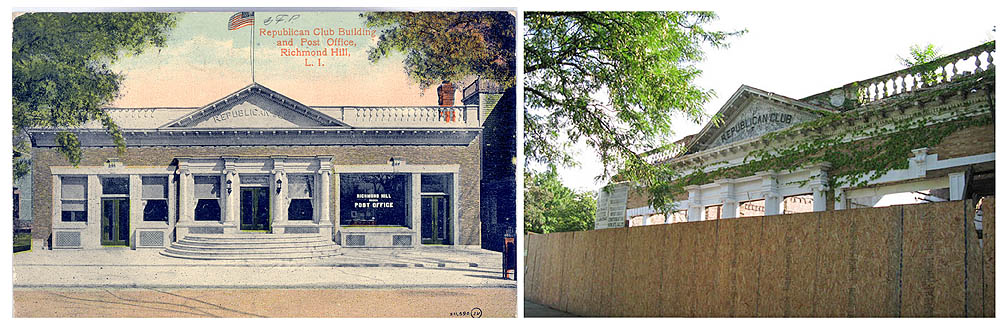

The structures primarily span from the Erie Canal era (1832, 211 Pearl St.) to modern times (NY Public School scaffolding planks c. 2005). Some are rare architectural treasures, others are rarely given a second look – but there wouldn’t be another building like it again. Every stick of lumber has a story to tell – whether about a building (862 Washington Ave., NY), a city neighborhood (1099 Leggett Ave., South Bronx), a structural icon (a Park Ave. rooftop water tank), a person associated with the site (P.S. 17, Henry David Thoreau School), or the timbers and trees themselves – prior to becoming the structural heart woods of a world class city.