ORIGINS OF ‘RECLAIMED’

To save and salvage seems basic to human nature, from early cave dwellers to the Bible, “Beat your swords into plowshares.” The names for it have varied over time – being termed “used, “repurposed,” “scrap” and “salvaged.” For hundreds of years, a popular term was “second hand.” It suggested the passing of an object from one human hand to another—central to the idea of reclaimed wood—but demoted it to sxxecond.

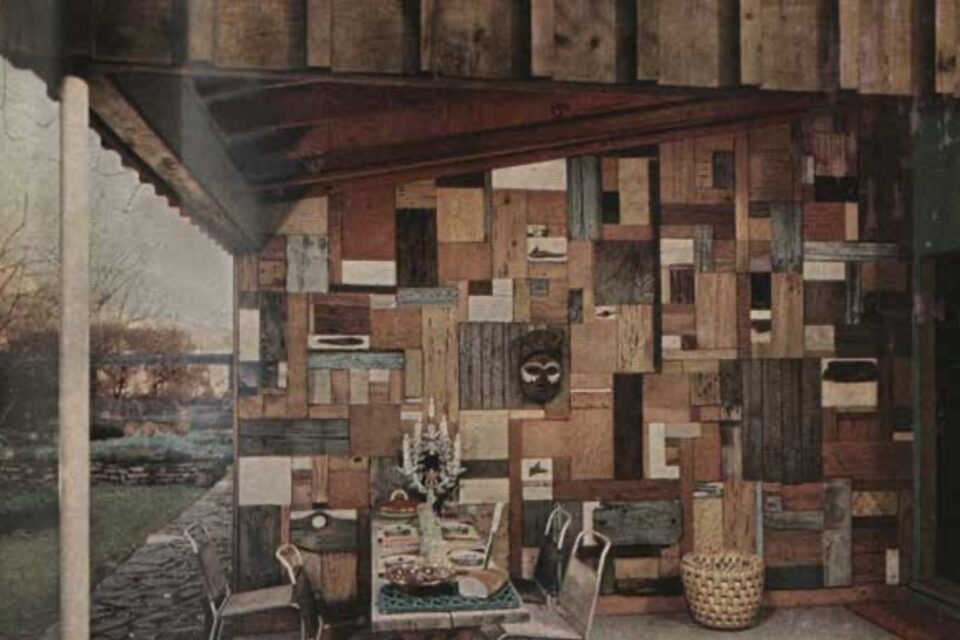

But after the WWII, something was starting to happen. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, magazines like House Beautiful featured stories of homeowners who found “beauty in the junkyard,” with profiles of interiors that included recovered wood and other materials.

The use of scrap in art goes back to the collages of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in 1910. A quarter century later, there were the combines of Robert Rauschenberg, John Chamberlain’s welded automobile parts, and Carl Andre’s minimalist reclaimed timber sculptures. (“The wood was better before I cut it than after,” Andre said. “I did not improve it in any way.”) Art had pointed to old things’ value as symbol and elevated their aged surfaces.

The origins of today’s interest in reclaimed wood can also be traced to the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Hippie activists launched voluntary recycling centers and co-ops and scoured used lumber yards and abandoned barns, to build and live as cheaply as possible. Books like The Whole Earth Catalog (1968) or Shelter by Lloyd Kahn (1970) spread the word.

The terms second-hand and used lumber no longer worked. Wood was being salvaged and re-manufactured, which explains how the term reclaimed wood came into use. The history of specific sites were being preserved through modern design. This was something new in the late twentieth century.

Some of the woods had been around for more than a thousand years. They’d come from virgin forests and carried the allure of old buildings. It’s a wonder that it took so long for the name to be reclaimed.

“The Wall” according to House Beautiful magazine (February 1953), “demonstrates the principle of free taste—an individual house for a very individual family.” It appears in their feature story on the home of mid-century modern designer Alexander Girard.