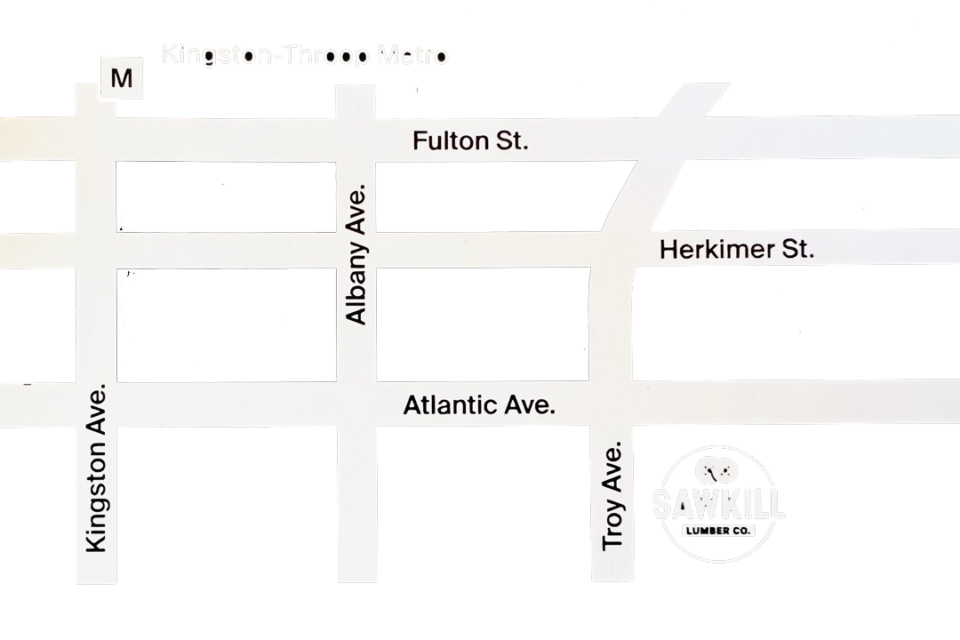

Our location at 71 Troy Avenue in Brooklyn includes a showroom, and a 3600 sf warehouse and wood shop. We are currently open for meetings by appointment. The space features a broad selection of over 40 antique, vintage and rare reclaimed woods.

(917) 862 7910

mailto:info@sawkill.nyc

Mon.-Fri. 9:00 – 5:30 pm

Sat. 10-4pm

71 Troy Ave.

Brooklyn, NY 11213

Please call in advance for appointment!

Getting There:

Train: A, C to Utica Ave. train stop. (approx. 8 min walk)

Car: Atlantic Ave. to Troy Ave. (1.5 mi. from Barclay Center)

Copyright © 2024 Sawkill NYC. All rights reserved.